The storage unit that changed everything cost me sixty-five dollars and a headache.

It was one of those March afternoons when the sky hangs low and heavy, like it can’t quite decide whether to rain or rip open. The auctioneer’s voice droned through the corridor of roll-up doors, bouncing off concrete and metal. People around me were sipping gas-station coffee and pretending this wasn’t all a little sad—bidding on the leftovers of lives that had run out of time and rent money.

The third unit on the left smelled like wet cardboard and old cigarettes. When the door rattled up, a wave of mildew rolled out. The crowd leaned forward as one organism, hungry for treasure and drama. All I saw were busted lamps, a stained mattress folded like a dead moth, a recliner that had lost a fight with a large dog, and boxes sagging in on themselves.

“Abandoned six months,” the auctioneer called. “Bidding starts at twenty.”

I don’t know why I raised my hand. Maybe it was the date—March 12th. Exactly twenty years since my brother left the house in a gray hoodie and work boots and never came back. Maybe it was the way the unit sat at the very end of the row, light pooling just short of its threshold, like even the sun didn’t want to step inside.

“Sold for sixty-five to the lady in the blue jacket.”

The key they put in my palm was cold and too small for what it was about to unlock.

I was supposed to be looking for a second-hand dresser and maybe a sofa that didn’t smell like a crime scene. Instead I spent an hour wading through other people’s leftovers. The lamps were useless. The recliner collapsed when I tried to move it. The mattress practically hissed when I cut the plastic off. I was about to chalk the whole thing up to bad impulse control when I saw the desk.

It was tucked in the back corner, cheap particle board, one leg bowed inward. The drawers stuck when I tried to open them, the tracks swollen with damp. I almost gave up. Then the bottom right one jerked halfway and stopped, locked on something.

I sat back on my heels, heart beating a little faster for no good reason, and tugged again. The drawer refused. It wasn’t swollen; it was locked. A cheap keyhole glinted through the flakes of rust.

I checked my pockets on instinct. I don’t know what I hoped to find—a miracle key that came with the purchase? Of course, nothing. Then I remembered the auctioneer flipping through a ring of mismatched keys, trying to match random locks for the crowd’s amusement.

I went back, found him loading his truck.

“Hey, sorry—do you still have those keys?”

He dug them out of his pocket and held them up like I’d asked for his firstborn. “You know none of these fit nothing, right? That’s the show.”

“Humor me,” I said.

Back in the unit, I knelt in front of the drawer and tried them one by one. Four slid in a little and stuck. Two didn’t even fit the hole. The seventh key turned.

Not smoothly, not like in the movies. It rasped, protesting years of neglect, then gave with a soft metallic sigh. The drawer crept open an inch, then another.

Inside, wrapped in a disintegrating grocery bag, was a shoebox.

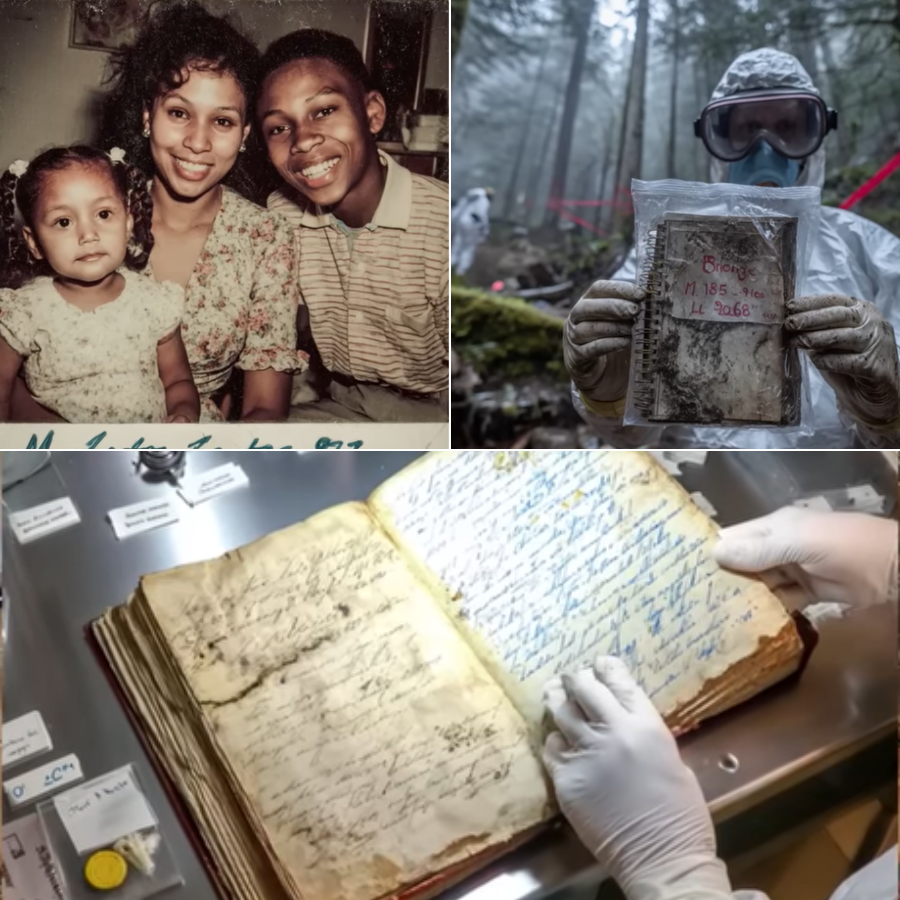

The cardboard collapsed in my hands, leaving a puff of dust and a memory of fresh rubber. Inside the box were three things: a water-warped composition notebook, its black-and-white cover peeling; a cassette tape in a cracked clear case with three handwritten words on the label—play when it rains; and a photograph of a boy in a gray hoodie, laughing at something just out of frame.

My brother.

The world didn’t tilt. The sky didn’t split. It was quieter than that. My knees just gave out, and I sat on the concrete floor of the storage unit with my heart shoving against my ribs, the smell of mildew and dust and something faintly sweet—old perfume?—pressing in. The photograph trembled in my fingers.

“Reuben,” I whispered.

It had been two decades since he walked out our front door in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, and vanished somewhere between our cracked front steps and a town that, as far as anyone could prove, did not exist.

Now I was holding his diary, dated two days after he disappeared.

To understand why my hands shook so badly, why my first impulse was to run and my second was to clutch that notebook like a life raft, you’d have to go back twenty years and stand in our little kitchen on Myrtle Street.

March 12th, 1988 had started like any other Saturday. The plastic clock over the stove blinked 7:03 in angry red numbers because the power had flickered overnight. The smell of eggs and toast hung in the air. Mama—Claudine Griggs—stood at the stove with her robe cinched too tight, stirring scrambled eggs like they’d personally offended her.

I was fourteen, all elbows and questions, fidgeting at the table with a textbook I had no intention of reading. The radio was on low, a gospel choir leaking through the static. Outside, a light drizzle made the world look like it had been erased and drawn again in softer pencil.

Reuben came down the stairs in his gray hoodie and scuffed work boots, the same ones he wore to his job at Washburn Printing. He was twenty then, taller than Mama, long-limbed and folded in on himself like he was always trying to fit into a space too small.

“Morning,” Mama said without turning around.

He bent and kissed her cheek. “Morning. Smells good.”

It was the peace in his voice that scared me later, looking back. At the time, I only half-noticed. I was busy stealing bites of toast and worrying about a math test.

“You working today?” Mama asked.

“No, ma’am,” he said. “Just gotta take care of something. I’ll be back by dark.”

He looked at me when he said it, just for a second. His eyes were that muddy hazel that changed color with the weather, and that morning they were soft, clear, like the air after a storm.

“You going where?” Mama pressed.

He smiled, that little crooked smile that never showed in posed photographs. “Nowhere, Mama. Just around. I’ll be back.”

He finished his eggs, rinsed his plate, and left his coffee half-drunk on the table. I remember that, the ring it left on the tablecloth. For some reason, that coffee stain occupied more space in my memory than the sound of the front door opening or closing.

He walked down the front steps into the gray morning and didn’t come home.

By noon, Mama had swept the kitchen four times. By three, she’d gone from muttering prayers to hissing his full name under her breath for making her worry. By seven, she’d turned the porch light on and sat on the front steps, arms wrapped around herself.

By midnight, she was calling hospitals.

At three a.m., she walked into the Pine Bluff Police Department in her nightgown and church coat, slippers soaked through, hair pinned crooked, and demanded to file a missing persons report.

The white officer at the desk looked at her like she was asking for the moon. “Ma’am, he’s what—twenty? He’s a grown man. Probably just blowing off steam. Let him cool down a day or two. He’ll come crawling back Monday, hungry as a dog.”

Mama slapped Reuben’s photograph on the counter. “My son is not a stray animal,” she said. “He didn’t take no clothes. No money. He didn’t tell nobody where he was going. Something is wrong. I want a report.”

They never filed one. Not really. They took his name and jotted it down somewhere. They said they’d “keep an eye out.” I watched Mama’s shoulders stiffen as she walked home in the cold, the curve of her back carrying something heavier than a missing son—carrying the knowledge that nobody who was supposed to help actually believed he was in danger.

The next morning I went into Reuben’s room to borrow his cassette recorder. I figured if I couldn’t sleep, at least I could record the sound of the rain and pretend it was something else. The room smelled like pencil shavings and laundry detergent and whatever cologne he’d started experimenting with.

The recorder was on his desk, but when I picked it up, a folded sheet of paper slipped out from between his sketchbook pages. My fingers went instantly cold.

There were only two lines on it, written in his careful block letters.

I’m going where I won’t be followed.

If I don’t come back, it means I found it.

“Found what?” Mama said over and over when I showed her the note. “Found what, Reuben? Found what?”

She refused to call it goodbye. She stuffed the note in an envelope, along with one of his sketches—a drawing of a wooden gate in a forest clearing, the words no roads, no clocks, just the hollow inked underneath. She took them to the station and slammed them down on the desk of anyone who would listen. Most didn’t.

There was only one man who did.

Detective Darnell McGee was one of the only Black officers in the county back then, a tall man with tired eyes and a wedding band he still twisted when he talked about certain cases. He listened to Mama. Really listened. He took the note, the sketch, the photograph.

“Did he ever mention a place called Sulfur Hollow?” he asked.

I watched Mama’s eyes narrow. “How you know that name?”

McGee told us he’d heard it once before, from an old man in a retirement home near Desha County. A story about a town that got “washed away.” He’d looked into it then and found nothing—no town charter, no land registry, nothing official. Just a faint pencil mark on a 1940s survey map: sulfur hollow, st. unknown.

Mama grabbed onto that name like it was a rope thrown into dark water. From that day on, Sulfur Hollow was the word that lived in the back of every conversation, the ghost at the table.

We were told it was just a story. Some backward superstition. We were told our boy had run off, maybe with drugs, maybe with a girl, maybe just with his own thoughts. People shook their heads and wagged their tongues and suggested suicide in whispers when they thought we couldn’t hear.

McGee quietly opened a file with Reuben’s name on it and put Sulfur Hollow in the subject line.

Then the years started to pile up.

Grief doesn’t arrive like a thunderstorm. It leaks.

First it was the way Mama left his room untouched. She washed his sheets every Sunday, even though nobody slept in that bed. She dusted his bookshelf and straightened his notebooks, those ragged composition books filled with drawings and half-sentences. She put fresh batteries in his cassette recorder and left it on his desk, like he might walk in any minute and hit record.

I hated that room. It felt like walking into a paused breath, like the whole world was waiting for a sound that never came.

By the time McGee retired in 1994, he’d solved dozens of cases, but not Reuben’s. He took that file home and locked it in a fireproof box under his bed, behind his Bible. He told me that much years later. “Some things you can’t let go,” he said. “Even when the job lets you go.”

Mama started losing her memory in 2002. At first it was small things—the stove left on, the keys in the freezer. By 2006, the doctor used words like “early-stage dementia” and “progression” and “care plan,” words that sounded clinical and calm and had no business being anywhere near my mother.

She forgot phone numbers, then dates, then the names of our neighbors. She forgot where she’d put her glasses, her purse, her mug. But she never forgot one thing. Every March 12th, she woke up and said, “Today is Reuben’s birthday.” It wasn’t. His birthday was in July. But March 12th was the last day she saw him.

Our lives reshaped themselves around her forgetting.

I moved to North Little Rock, had a daughter of my own—Micaiah, with my brother’s eyes and my stubbornness. She grew up pointing at the framed photo in Mama’s living room and asking, “Who’s that man, Grandma?”

“That’s my boy,” Mama always said, clear and sharp and present in that one sentence in a way she often wasn’t for anything else. “That’s my Reuben. He found something nobody else could see.”

Back then, I thought she was just protecting herself. A story is easier to live with than a void.

Then I found his diary in a shoebox in a storage unit that should’ve been nothing but junk.

I didn’t drive straight home from the auction. I drove to the only place I could imagine taking something like that.

McGee answered his door in his slippers, his hair more gray than I remembered, his shoulders broader with age, but his eyes still sharp.

“Valina?” he said, surprise and something like dread mixing in his voice. “You all right?”

I held up the shoebox. My hands were still shaking. “I found Reuben’s diary.”

For a long second, he just stared at the box. The quiet between us stretched thin as glass. Then he stepped aside.

“Come in,” he said. “And start from the beginning.”

His living room smelled like old books and lemon oil. There was a cross-stitched Bible verse on one wall and a faded framed commendation from the force on another. A ceiling fan ticked overhead, the same hesitant rhythm it had when I was a kid sitting on that couch with my dangling legs, listening to grown people talk in circles around the words “cold case.”

Now I was the grown person, and my hands were the ones peeling back the lid of the shoebox.

The notebook inside looked like it had been left in the rain and given up on. The cardboard cover was warped, edges curling. Pages had stuck together in places. But the handwriting inside was as familiar as the sound of my own name.

The tape lay beside it in its cracked case, the words play when it rains written in Reuben’s meticulous block letters. He’d always printed like that, as if even his handwriting were an illustration.

McGee picked the notebook up carefully, like it was something that could bite. He flipped to the inside cover, where Reuben had written his name and the year:

REUBEN LAMONT GRIGGS

1988

A chill ran down my spine. My brother’s name. My brother’s year.

“Valina,” McGee said slowly. “Do you know what day he disappeared?”

“March 12th,” I said.

He turned a few pages, scanning the dates Reuben had scrawled in the top corners. Then he stopped.

There it was. March 14th, 1988. Two days after Reuben walked out of our house and dissolved into rumor.

“There shouldn’t be anything after the twelfth,” I whispered. “There shouldn’t be anything.”

McGee’s finger traced the date. “But there is.”

He read in silence for a minute, his brows knitting, his lips tightening, then relaxed. Whatever he saw there wasn’t panic. It was something else—recognition, maybe, or resignation.

“Before we go any further,” he said, closing the book gently, “you need to know something. I kept your brother’s file. I never could quite stomach how it was left. Over the years I…checked some things. Looked into a few stories.”

He stood up, crossed to a bookshelf, and pulled down a battered fireproof box. From inside it, he took a Manila envelope that had yellowed at the edges. He spread its contents on the coffee table: a photocopy of an old county survey map, a newspaper clipping, some handwritten notes.

On the map, in faint pencil at the edge of Lincoln County, was a name I’d seen a hundred times in my nightmares. Sulfur Hollow. No coordinates. No road lines leading in or out. Just a ghost of handwriting.

“That mark right there is all we ever had officially,” McGee said. “No census records. No land deeds. But I kept hearing it come up. Old folks in Desha talking about revivals out in the woods. People vanishing. The land being ‘reclaimed’ by the state. Every time I tried to follow it, the paper trail just…stopped.”

He slid the newspaper clipping toward me. The date at the top read July 1952. The headline, in jagged black type, said:

EIGHTEEN VANISH FROM OUTDOOR REVIVAL NEAR SULFUR HOLLOW

I read the article twice. It talked about a traveling preacher named Alence Glee, beloved in Black congregations for his “prophetic intensity” and “claims of divine thresholds.” It described an outdoor tent revival held on disputed farmland. On the third night, according to the sheriff’s statement, the preacher and eighteen congregants were “unaccounted for” when neighbors went by in the morning. No tire tracks. No footprints. No bodies. The land, the article noted, was designated for “state use” the following year.

“Never heard about that,” I said, my voice hoarse.

“It never made the big papers,” McGee said. “And no one with power wanted to agitate church folk with talk of vanishings.”

He opened the diary again and flipped through pages filled with sketches: trees bending like claws, spirals carved into stones, what looked like a gate half-buried in earth, circular clearings. In multiple drawings, a man in a white suit stood near water, or near a pay phone, or at the edge of a road that vanished into blankness. His face was always turned away or left smooth and featureless.

Above one sketch of a wooden arch in a hillside clearing, Reuben had written: no roads, no clocks, just the hollow.

“That phrase ring any bells?” McGee asked.

I nodded. “Otis told me he and Reuben were working late at the print shop one night. Reuben showed him a drawing of a gate like that, and under it he’d written the same words. Otis asked him where it was. Reuben just smiled and said, ‘Not here. But not far.’”

Otis Tillery had been my brother’s best friend since junior high, a broad-shouldered boy with ink on his fingers and music in his bones. He still ran a tiny screen-printing operation out of his garage, still lived two streets over from where we grew up. He’d carried his own guilt for twenty years—guilt for not asking more, for not following Reuben that day.

McGee turned to the back of the diary, to the entry dated March 14th. The ink had bled at the edges, like it had been written in humidity.

If you find this, I’ve already crossed, it read.

I didn’t leave because I hated life.

I left because I saw something more.

We sat there, the ceiling fan ticking overhead, the words hanging between us like a sentence waiting to be carried out.

“Where did you say you found this?” McGee asked quietly.

I told him about the auction. The busted desk. The locked drawer. The way the key had turned with that reluctant sigh. I showed him the cassette with its handwritten instruction: play when it rains.

He frowned. “That’s not coincidence,” he said. “That’s timing.”

Outside, rain began to tap against the windows. A low, rolling storm, the kind that makes the air taste like pennies.

McGee went to a closet and came back with an old Magnavox cassette player, yellowed plastic and peeling stickers. “Let’s see what he left us,” he said.

We waited until the rain found its rhythm.

It started as a scattered percussion on the roof, a few exploratory drops on the glass. Then it settled into a steady, insistent drumming that filled the spaces between the ticking fan and our own breathing. The house felt enclosed, wrapped in water.

McGee slipped the tape into the player and pressed it in with a click that sounded too loud. For a moment there was only static, a soft white hiss like distant ocean. Then a voice rose out of it, warped at the edges but unmistakable.

Reuben.

“If you’re hearing this,” he said, “it means I didn’t come back.”

His voice sounded like it always had when he was trying to explain something I was too young to understand—calm, almost detached, with that slight upward lilt at the end of sentences, testing my attention.

“But don’t cry for me,” he went on. “I didn’t run. I saw something in the trees. It knew me. It called me by name.”

I pressed my hand over my mouth. My heart pounded in my ears.

“I met a man named Alence,” Reuben said. “He wears white and smells like lilies. He told me there’s no time there. No clocks. Just the hollow. Said if I followed him, I’d understand what I’ve always felt but could never explain.”

The tape clicked. Silence swallowed the room.

I realized my nails had dug crescents into my palms. McGee stood in the doorway, his face pale.

“He made another tape once,” McGee said. “Back in ’87. Left it at the print shop. Otis told me it was just river noises and whispering. When he asked about it, Reuben laughed and said, ‘It’s not a river. It’s a door.’”

Thunder rolled somewhere distant, coming closer.

The past, which had sat heavy and inert in my life for so long, had just shifted. It wasn’t still. It was moving toward us.

“How far is Bayou Bartholomew from here?” I asked.

McGee looked at the map already forming in his mind. “About an hour in the truck,” he said. “Then a couple hours on foot if the old logging road’s gone to hell like I think.”

“Let’s go,” I said.

He studied me. “Valina, that land’s old. Folks left it alone for a reason. The roads are grown over. The only way in is on foot, and even then—”

“My brother walked in alone,” I said. “I can at least walk in with answers.”

He didn’t argue again.

Outside, the rain picked up, begging the tape to be played again. We left it on the table and stepped into the storm.

By the time we reached the edge of the forest, the rain had thinned to a mist. The sky was the color of dirty dishwater, and the air smelled like wet leaves and rust.

McGee’s truck rattled over the last stretch of gravel road, tires groaning in protest. He parked where the path narrowed into underbrush and shut off the engine. The quiet that followed was almost jarring.

“You sure?” he asked one last time.

I opened the door and stepped down. My boots sank half an inch into the mud. “I’ve been waiting twenty years,” I said. “I’m not going to change my mind now.”

He grabbed a backpack from the cab—water bottles, first-aid kit, flashlight, an old Smith & Wesson wrapped in a rag, and a photocopy of the 1949 survey map. The faint pencil mark for Sulfur Hollow hovered near a scrawl of the words BAYOU BARTHOLOMEW.

We walked.

At first the woods sounded alive—crows arguing in the distance, small things scurrying in the underbrush, branches creaking as they shrugged off the last drops of rain. The path, such as it was, wound between pines and oaks, their roots bulging from the ground like knuckles.

I kept my brother’s diary tucked under one arm, my fingers unconsciously tracing the spine. Every few minutes I would open it and glance at the sketches—spiraled stones, a ravine, a wooden arch.

After an hour or so, the sound changed.

I didn’t notice it all at once. It was more like realizing a song on the radio had faded out without you catching the last note. The bird calls thinned, then disappeared. The wind that had been shushing through the leaves like a mother soothing a child stilled.

“Do you hear that?” I whispered.

McGee paused and listened. His brow furrowed. “I don’t hear anything,” he said.

“Exactly.”

The silence was thick, oppressive. It had weight. My ears felt like they were popping on a descending plane. I swallowed, but the pressure remained.

“Places like this exist,” McGee said quietly. “My cousin Vernon, he was a surveyor out here in the seventies. Told me there were clearings where the air felt wrong. Said your ears would ring from how quiet it was, like the world turned the volume down just there and nowhere else.”

We kept walking.

The forest floor grew wetter, then drier, as if we’d crossed an invisible boundary. A shallow ravine cut through the earth ahead, choked with vines and brambles. On the far side, half-buried in soil and moss, was a curve of dark, rotted wood.

From a distance it looked like the remains of a fence. Up close, as we pushed through the thorns and climbed, it became something else.

An arch.

Or what was left of one.

Two beams jutted from the earth at a bent angle, forming a rough half-circle, the top plank long since collapsed. The wood was gray and pitted, almost part of the earth that held it.

“There should’ve been buildings,” McGee murmured. “Foundations. Chimneys. A well, at least. But it’s like they cut the memory out of the land.”

I stepped closer. Someone—years ago, decades maybe—had carved words into the top beam. Dirt and lichen filled the grooves, but when I rubbed with my sleeve, they emerged slow, like a photograph in developer fluid.

NO ROADS

NO CLOCKS

JUST THE HOLLOW

My knees almost gave out. I flipped open the diary with shaking hands. There it was—Reuben’s drawing of the same arch, down to the curve of the beams and the angle of the hillside. Underneath, in his handwriting: no roads, no clocks, just the hollow.

“He was here,” I said. My voice came out thin. “McGee, he was here.”

He didn’t answer. He was scanning the treeline, the ground, the sky, as if expecting something to step out of the space between trees.

A few yards beyond the arch, under the spreading arms of an oak, a flat stone lay flush with the earth. Not natural. Cut. About two feet wide. Moss obscured most of its surface.

I don’t know how I saw it. Maybe the diary had tuned my eyes to spiral patterns and edges the way a new language tunes your ears.

I knelt and brushed the moss away. My fingers found grooves, shallow but deliberate.

Three letters emerged, faint but legible.

RLG.

Reuben Lamont Griggs.

My heart stopped, then slammed back into motion so hard it hurt.

“Reuben,” I whispered, and the sound was strange in the empty air.

My fingers dug deeper, scraping away dirt to reveal more carving.

YOU’LL KNOW WHEN IT’S TIME TO COME HOME.

Tears blurred my vision. I pressed my palm flat against the stone, over his initials, over that impossible message. The moss was damp and cool. The stone itself felt…warm.

Something tugged at the edge of the stone, a hint of color that didn’t belong there. I pinched it between my fingers and pulled.

A strip of fabric came free, clotted with dirt. I shook it out, and it unraveled into a tattered sleeve. Gray. Hoodie material. Stained with time.

I didn’t need anyone to tell me whose it had been.

I started to cry then. Not the jagged, choking sobs grief usually tore out of me, but something quieter, deeper. McGee stood a few feet back, his face turned away to give me space. The forest pressed in, listening.

“He didn’t just vanish,” I said finally, wiping my eyes on my sleeve. “He crossed something. Right here.”

McGee nodded slowly. “Your mama came to my office one afternoon in ’88,” he said. “She was shaking so hard she could barely hold her purse. She told me, ‘I know he’s not gone. He just found someplace I can’t reach yet.’ At the time I thought it was denial. Maybe it still is. But standing here…”

He let the sentence trail off.

Thunder grumbled distantly again, closer now. The air thickened.

“We should head back,” he said. “Storm’s rolling in.”

“Give me a minute,” I said.

I sat with the stone, the hoodie scrap clutched in one hand, the diary in the other. For the first time in twenty years, I didn’t feel like I was chasing a shadow. I felt like I was standing toe-to-toe with whatever had taken my brother.

It didn’t feel evil. It didn’t feel benevolent either. It felt…indifferent. Ancient. Like a seam in the world that had been there long before us and would be there long after we were gone.

On the way out of the forest, cicadas began screaming all at once.

The sound hit us like a wave. One moment, silence. The next, a shrill, layered chorus, so loud I flinched.

“Forest exhaled,” McGee shouted over the noise.

I wasn’t sure if he meant it as a metaphor.

Back in town, life snapped back into its grooves. The grocery store parking lot, the kids on bikes, the pastor on the corner in his shiny shoes. The regular world felt thin, like wallpaper over a door.

I called Otis as soon as I got home.

“We found it,” I said, standing in my kitchen with dirt still under my nails. “The hollow. The gate. There’s a stone with his initials, Otis. He carved…something. Or someone did.”

Otis was quiet for a long heartbeat. Then he exhaled a sound that might’ve been a laugh or a sob. “I believed him,” he said. “All those years. I just didn’t know what to do with it.”

I told him about the diary, the tape, the man in white. About the way the air felt wrong out there. About the sleeves of Reuben’s hoodie coming up through the dirt like it had been waiting to be pulled free.

“Remember when Reuben said the hollow wasn’t a place?” Otis said. “That it was a moment?”

“Yeah,” I said.

“I think he meant it.”

The man in Reuben’s diary had many names.

Sometimes Reuben called him the man in white. Sometimes the threshold preacher. Sometimes just A.

He drew him over and over in the last third of the notebook—tall, thin, in a crisp white suit that didn’t wrinkle. Sometimes he held a briefcase. Sometimes a worn leather Bible. In every drawing, his head was either turned away, obscured by shadow, or left smooth and featureless.

Saw him again by the church fence, one entry read in Reuben’s looping script. No footprints. No birds singing when he’s near. Told me the place between places is close. Said I’m almost there.

On another page, taped in with yellowed Scotch tape, was the old newspaper article about the 1952 revival. Above the preacher’s name, Reuben had scribbled in the margin: same man. always near water.

I took the clipping to McGee. We scanned it on his ancient printer, adjusted the contrast as best we could. The man in the grainy photograph—dark suit, hands lifted, face turned upwards mid-sermon—was blurred, but something in the angle of his shoulders, the tilt of his head, matched Reuben’s sketches unnervingly.

“If Alence Glee from ’52 and your brother’s ‘Alence’ are the same…” McGee began.

“They are,” I interrupted. “Reuben didn’t just make him up.”

There was only one place in town I could think to ask about a preacher from half a century ago.

Mount Calvary Tabernacle sat between a vacant lot and a rundown liquor store in Little Rock. The paint peeled from its clapboard siding. The steeple leaned a little to the left, like it was listening hard. The doors, though, were open, and the music spilling out was alive.

A woman in a lavender head wrap met us on the steps. Her eyes were the color of bitter chocolate, sharp and tired.

“You here for the choir or the pantry?” she asked.

“Neither,” I said. “We’re looking into something from a long time ago. A preacher named Alence Glee.”

Her face hardened in an instant. The warmth of hospitality vanished.

“We don’t say that name in this building,” she said.

McGee held up his hands. “Ma’am, we’re not here to stir trouble. Just trying to understand if anybody’s seen a man in a white suit. Tall, shows up near—”

“Near water,” she cut in. “Near the fence. Across the street. Standing under the streetlamp before service. No footprints. No sound when he moves, if he moves at all.”

“You’ve seen him,” I said.

She nodded once. “First time when I was eight. My grandma grabbed my face, turned it away, and said, ‘Don’t look at that man. That’s someone else’s messenger.’ Pastor told us he was just a drifter. But drifters walk. He just…appears. Always outside. Always watching. Never comes in.”

She stepped back into the doorway. “My mama said he followed folk who couldn’t put their dead down. You be careful what you call back with all that looking.”

We thanked her and left. On the sidewalk, I could feel eyes on my back. When I turned, no one was there. Just a smear of light on the opposite corner where a streetlamp fizzled on in the daytime gloom.

That night, after Micaiah was asleep and the house had gone still, I took out a small metal lockbox from the back of my closet.

Inside were things I’d promised myself I was done needing: a folded note I wrote to Reuben when I was ten, apologizing for breaking his cassette tape and promising to buy him a new one when I “got rich”; a broken necklace he’d given me at twelve; a plastic token from a pay phone we used to play pretend with.

The token had a little bell etched into one side, a company logo long out of business. I spun it between my fingers, thinking of Reuben’s sketches of pay phones and drainage ditches and water.

In one drawing, he’d drawn a phone booth standing ankle-deep in a flooded ditch. The caption read: Water Street & Guyver Springs. He’d drawn the man in white leaning casually against the booth’s frame, head bowed as if listening.

I typed the cross streets into an online map. The intersection came up in a few seconds. No pay phone. Pay phones had gone the way of cassette tapes and believing the police would care about a missing Black boy who liked to draw. But the building beside it, a shuttered laundromat with boarded windows, was still there.

The sky the next morning was the same heavy gray it had been the day he left. I drove to the intersection anyway, telling myself I was just…checking. Not expecting anything. Definitely not expecting my dead brother to call me from a phone that didn’t exist anymore.

The concrete slab where the booth used to stand was still there, a rectangle of discolored pavement near the curb. The metal bolts that had once held the structure in place were rusted stumps.

I stood on the slab, hands in my jacket pockets, feeling foolish and stubborn and a little bit scared.

“Reuben,” I said aloud, my voice swallowed by traffic. “If you wanted me here, you better make this worth the gas.”

My cell phone rang.

It wasn’t my normal ringtone. It wasn’t any tone I recognized. It was a high, clear chime, like a small bell rung underwater. The screen stayed black. No caller ID. No number. Just the vibration in my hand and that otherworldly sound.

I answered.

“Hello?”

For a moment, there was nothing. Then a soft static, like the beginning of the tape. Then humming.

Not words. Not a melody I could name. Just a low, rising tune, familiar in the way smells from childhood are familiar—bypassing logic and going straight for the part of the brain that remembers the color of your first bike and the pattern on your grandmother’s kitchen curtains.

Reuben hums when he can’t sleep, I thought, my chest tightening. He’d hummed that exact pattern lying on his back on the roof, watching the stars. He’d hummed it when he was bored, drawing in the margins of his notebooks. He’d hummed it when Daddy died, lying on the floor of his room in the dark.

My knees buckled. I sank down, right there on the edge of the concrete slab, phone pressed to my ear, eyes squeezed shut. The humming went on for maybe thirty seconds. Then it stopped. The line went dead.

I sat and cried in the shadow of a vanished phone booth while morning commuters blew past, oblivious.

Across town, at that same moment, McGee opened his front door to fetch his paper and found an envelope on his doormat. No stamp. No return address. Just his name in neat, unfamiliar handwriting.

Inside was a strip of thick paper, torn from what looked like a Bible page. On it, in red ink, seven words were written in a hand that tilted like Reuben’s but wasn’t quite his.

Tell Valina he was never alone.

Grief rearranges itself when it gets new information.

For twenty years, my grief had been shaped like a hole in the ground. An absence. A door slammed so hard it had disappeared into the wall. After the forest and the phone call and the envelope, my grief changed shape. It was still heavy, but it wasn’t a hole anymore. It was a doorway left ajar.

That night I sat at Mama’s old kitchen table in her house on Myrtle Street, the diary open under the lamp. The rest of the house was dark. The air smelled faintly of furniture polish and the cinnamon candles she used to burn on Sundays.

Until then, I’d only skimmed Reuben’s later entries, too scared of what I might find, too overwhelmed by what I had. Now I read them slowly, cover to cover, like letters mailed to me across decades.

His earlier diaries had been messy things—half-thoughts, doodles, snippets of conversations, grocery lists mingled with sketches of hands and gates and faces. But starting March 1st, 1988, something changed. The handwriting steadied. The fragments became full sentences.

I know this will be hard to believe, he wrote on March 3rd. Maybe you’ll think I lost my mind. But I need you to know I was more awake out there than I’ve ever been.

He talked about pressure in his chest that followed him into sleep, a sense that the world had seams and he’d started to feel where they were. He wrote about seeing the man in white—Alence—for the first time near the train tracks.

He doesn’t move his feet, Reuben wrote. He just…is where he is. When he looks at you, you remember things. Not like memories you’ve forgotten, but like someone rearranged them and handed them back so you could see them from the outside.

He described the smell of lilies. The hush that fell over birds when the man appeared. The way shadows seemed thickest where he stood.

On March 10th, he wrote: He told me the hollow isn’t a town. It’s a moment you can step into if you’re paying attention. Said some people find it by accident when the grief gets too heavy—when they stand very still at the edge of some old pain and listen long enough. Said I’ve been listening since Daddy died.

Daddy. The word still felt raw, even after all those years.

Our father had died in 1983—heart attack in a borrowed truck on Highway 11. He was alone when it happened. Reuben, seventeen and soft-faced, had to go to the morgue to identify the body because Mama couldn’t stand up without shaking.

He came home from that sterile room smaller somehow, as if the world had taken a bite out of him and forgotten to spit it back out. He’d sat on the roof that night, staring at nothing, humming the tune that later came through my phone on a dead line.

On March 11th, 1988, Reuben wrote: I think Sulfur Hollow is where Daddy went when he wasn’t ready to leave us but his body gave him no choice. Maybe the hollow is a mercy, a space between stories where the unfinished can rest.

On March 12th—the day he left the house—he wrote only one line: If the door opens, I’m stepping through.

On March 14th, the entry I’d already read once and now read again with trembling hands:

You’ll think I disappeared, but I didn’t. I stepped sideways. In the hollow there’s no pain, no clocks, no guilt. I waited for someone to come looking, but I knew it would be you, Vel. You were always the one who listened between the words. I’m sorry I left you, but I didn’t forget you.

Sometimes I see Mom lighting candles. I see Otis listening to records. I see you folding paper stars like we used to. These aren’t dreams. They’re echoes. The hollow lets you watch without touching. I wish I could tell you this face to face. But if you’re reading, it means you followed the thread I left. It means you’re ready to let go. I’m not lost. I’m just waiting.

The last page had no date, just a page number and one sentence, pressed so hard into the paper that the indent showed through the next sheet.

You’ll know when it’s time to come home.

The period at the end was smudged, as if he’d hesitated.

I closed the diary and laid my palm flat on the cover. The lamp hummed softly. Outside, the cicadas screamed, then fell abruptly silent, as if someone had flipped a switch.

Two days later, Mama died.

She’d been fading for years, her memories fraying like old lace. Some days she’d look at me and see the little girl with mismatch socks. Some days she’d call me by her own mother’s name. Some days she sat for hours in front of Reuben’s photo, thumb stroking the glass, murmuring prayers I couldn’t quite catch.

On the night between our trip to the hollow and my long reading at the kitchen table, she was unusually lucid. She called to tell me she’d lit a candle for him.

“For both my babies,” she said. “For the one in my house and the one out there in the trees.”

“Out where, Mama?” I asked, even though I knew.

“In that quiet place he found,” she said calmly. “The one with no clocks. You go on and let him be there, you hear? Don’t you drag him back into this noisy world. Some places ain’t on maps for a reason.”

That was the last real conversation we had.

She passed away sometime before dawn, sitting in her armchair with the candle still flickering low and Reuben’s photograph in her lap. Her hands were folded, her expression peaceful, like someone finally stepping into a room where the light felt right.

When they called to tell me, I didn’t cry.

I sat on the edge of my bed, the diary on my nightstand, and whispered, “He’s waiting for you, Mama.”

Outside my window, a lone cicada screamed once, then stopped.

We went back to the clearing one more time.

This time, Otis came with us. He brought his camcorder, an old thing with a stubborn red record light, and a backpack full of water and sandwiches and nervous energy.

The trail was easier the second time, as if the forest remembered our feet. McGee had gone out the day before with a machete and tied strips of red cloth to branches at intervals. None of us commented on how the cloth faded quicker than it should have, as if the trees were drinking the color out of it.

The air in the basin was still wrong, but I’d grown used to that wrongness. It felt almost…familiar. Like the pause between inhale and exhale.

The stone with Reuben’s initials waited under the oak. The gray hoodie scrap lay where I’d left it, damp but unchanged. Claudine’s thin silver prayer charm—her only real piece of jewelry—glinted faintly at the base of the stone, where I’d placed it after she died.

“This is it?” Otis whispered, panning the camera slowly. “This is where he…left?”

“I don’t think he died here,” McGee said. “I think he just…took a different road.”

“There are no roads,” I said, touching the arch remnants. “That’s the point.”

I’d brought Reuben’s diary in a plastic case, wrapped in an old T-shirt. I held it for a long moment, thumb rubbing the frayed cardboard through the plastic.

“This belongs here,” I said.

I knelt and dug into the earth beside the stone with my hands. The soil was cool and soft, like it had been turned recently, though I knew it hadn’t. Otis handed me his pocketknife, and I used the tip to loosen roots and carve a space just big enough for the case.

We laid the diary in the ground, all that ink and graphite and longing, all those maps and sketches and words, and covered it gently. The earth settled over it with a sigh I felt more than heard.

I wiped my hands on my jeans and turned the knife over in my fingers. On the other side of the slab, where the stone was bare, I began to carve.

The letters came slowly, awkwardly, but they came.

VLG

2008

Valina L. Griggs. The year I finally stopped standing at the edge of a vanished town and walked away.

I stepped back. The stone now held both our names, spaced decades apart, carved by different hands but connected by the same hollow.

A soft breeze brushed my face. For a second, the air tasted like lilies and cigarette smoke and cinnamon candles and something else I couldn’t name.

Otis raised the camera and framed the shot silently.

“People are going to think we made this up,” he muttered. “Like some folktale we cooked up for YouTube.”

“Let them,” McGee said. “Maybe we’re not supposed to explain it.”

On the drive back, the sky finally made up its mind and let the rain fall.

The letter came three days later.

No stamp. No return address. Just my name in handwriting that leaned like it had somewhere to be.

Inside was a square of parchment, thick and soft. The edges were singed a little, as if it had been held too close to a flame. In the center, in Reuben’s careful block letters, were eight words.

THE TOWN NEVER NEEDED A MAP.

IT JUST NEEDED MEMORY.

I laughed. Not because it was funny, but because it felt exactly like him—half joke, half sermon, all heart.

I put the parchment in Mama’s Bible, between Psalms and Lamentations, where she’d tucked every grief she’d ever had.

Sometimes, late at night when the cicadas start up and the house is very quiet, I stand at the kitchen window and listen for humming. Sometimes I swear I hear it, just for a second, threaded between the refrigerator’s drone and the ticking clock.

I don’t look for Sulfur Hollow on maps anymore. I know better now.

It’s not a dot or a set of coordinates. It’s a seam in time, a moment where grief and love and memory press so hard against the skin of the world that it gives way a little. Some people find it in a forest clearing. Some at the edge of a phone that doesn’t ring anymore. Some in the doorway of a house where someone should be and isn’t.

My brother stepped through one of those seams twenty years ago. For a long time, I chased him, trying to drag him back onto the side of the world with addresses and street signs and missing persons reports that never got filed.

Now I just remember him.

And in remembering, I keep the town that doesn’t exist exactly where it’s supposed to be: not on paper, not in GPS, but alive in the hollowed-out space between one generation and the next.

My daughter asks me sometimes, “Mama, do you think Uncle Reuben is in heaven?”

I tell her the truth as I know it.

“I think he’s in a place where there are no clocks,” I say. “No roads. Just the hollow. And I think, every once in a while, when it rains, he listens to us the way we listen for him.”

She tilts her head like she’s trying to hear something too.

We stand there together, at the window, watching the water turn the street into a rippling mirror, and for a heartbeat I swear I hear it—the soft scratch of a pen on damp paper, somewhere just beyond the edge of what this town remembers.